Acclaimed travel writer Kendall Hill, explores one of the world’s truly extraordinary destinations that’s ripe for the culturally curious traveller and lover of luxury hotels.

Arriving in Bhutan is like touching down on another planet. It’s not just that this tiny Himalayan kingdom is more beautiful than anywhere else you might have seen on Earth. It’s also because life is so blissfully free of the ills plaguing western society that our lifelong dream of “getting away from it all” is, in fact, possible here.

Among the country’s vertiginous virgin forests of blue pine, hemlock and rhododendron there is no evidence of overdevelopment, environmental abuse or globalisation, because they are forbidden under Bhutan’s acclaimed Gross National Happiness (GNH) policy.

GNH is much more than a catchy marketing slogan. In practice, every law is first vetted by a select committee to ensure it won’t harm the people’s contentment or quality of life. As the GNH website says, “The future cannot be what it brings to us, it must be how we want it to be.”

The dogma has resulted in some fascinating – and admirable – firsts for this remote realm of 750,000 people. There is a total (but not totally effective) ban on smoking, because tobacco is “detrimental to physical and spiritual health”. Medical care and education are free. The constitution decrees at least 60 per cent of the country must be covered by forest, forever. As a result, Bhutan is the only carbon negative nation on the planet.

In this blessed land it is also forbidden to hunt, to mine, and even to burn trees for cooking and heating – rural dwellers are given free electricity instead. The Bhutanese Government has also pledged to produce 100 per cent organic food by 2020, and zero waste by 2030.

“We are tucked away in the world’s highest mountains,” explains Sangay Wangchuk [correct], brother-in-law of the king, Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck [correct].

“What’s not sustainable is not going to last.”

From their Himalayan eyrie the royal family and 72-member parliament can look down on the world’s great social models and assess what’s worked and what’s failed. “The trial and error has already been done for us,” Wangchuk says.

Bhutan has managed to preserve its unique culture and traditions by limiting contact with the outside world. The first outsiders were admitted only in 1974 but foreigners are still scarce today thanks to a “high value, low impact” tourism protocol that demands visitors spend a minimum USD250 a day. It’s a small price to pay to discover the Dragon Kingdom.

It’s hard to know where to begin when describing this remarkable place. Do you start with the prayer wheels that are everywhere and every size and spin perpetual goodwill over the land? Or the houses painted with fabulous creatures like snow lions and garudas (and, yes, sometimes giant phalluses – to keep the evil eye at bay)? Or the fact that mindfulness – driglam namzha, “the conscious pursuit of harmonious living” – underpins Bhutanese culture?

Not to mention the fantastic real animals that dwell in the mountains, such as red pandas, blue sheep, snow leopards, tigers, one-horned rhinoceroses and the national mascot, a bizarre goat-antelope hybrid called the takin.

The bonus of Bhutan’s elitist admissions policy is that visitors tend to be “sophisticated and educated”, in Wangchuk’s words. They also tend to have wads of money so another thing this country excels at is exquisite, expensive accommodation.

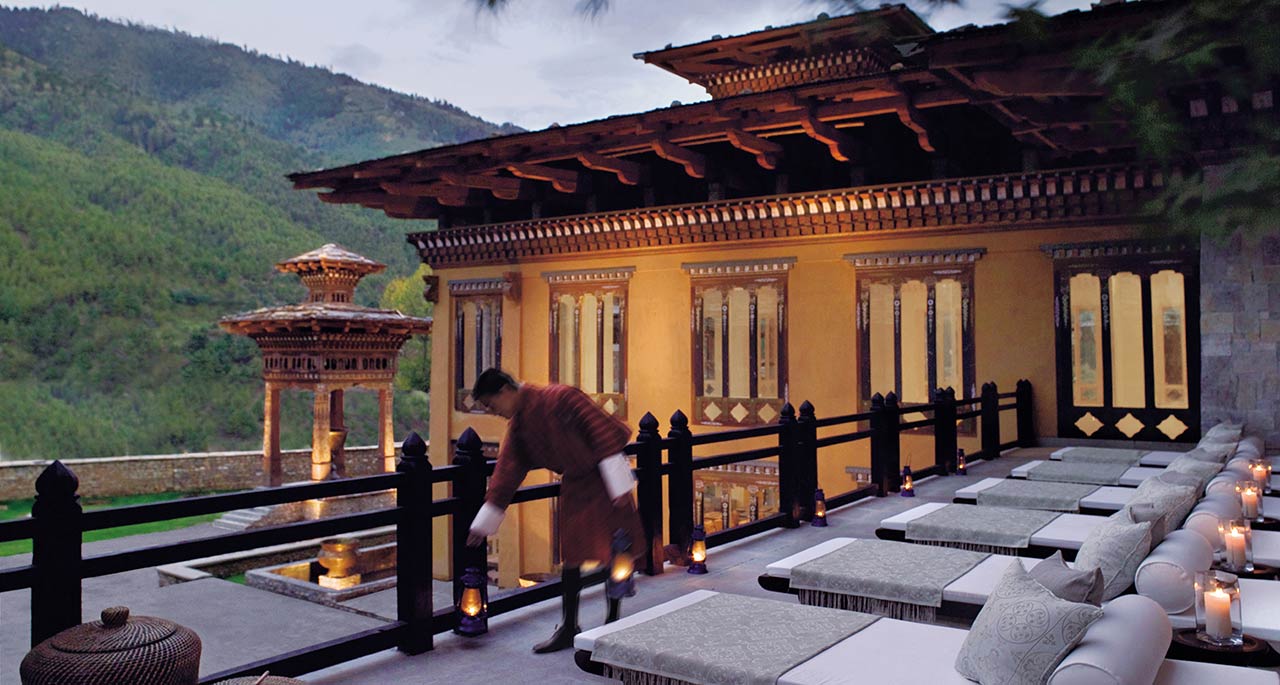

Aman Resorts was the first luxury operator to land here, opening a circuit (kora) of lodges in the five valleys – Thimphu, Paro, Punakha, Gangtey and Bumthang. All suites at the Amankora inns are identical, which seems unimaginative but if you are lucky enough to stay in one of these hemlock-lined zen cubes with bukhari wood burners and misty valley views, there will be no complaints. www.aman.com

Uma by Como has a pair of lovely hotels at Paro and Punakha www.comohotels.com and Wangchuk is building five exceptional properties, set to open mid-year, that will be managed by Six Senses www.sixsenses.com

Not everything in Bhutan is perfect. The roads can be atrocious and the cuisine is an acquired taste, from the ubiquitous ema datsi, braised chillis drizzled in cheese, to soju tea the colour of dilute blood.

But the humble Bhutanese are the first to concede their ancient homeland is still a work in progress.

“We haven’t got everything correct,” admits Wangchuk, “but all in all we are far better off than most places on Earth.”

More at tourism.gov.bt

Miele for Life contributor, Kendall Hill, is one of the country’s most well regarded journalists, editors and critics. For the past decade he’s been a regular freelance travel and food journalist for Gourmet Traveller, The Australian, Qantas Magazine and The Australian Financial Review.